The author has included a content warning for the story below: Discussions and depictions of suicide and suicidal ideation.

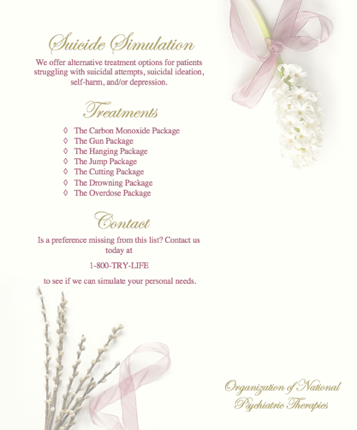

When I take my teenage daughter to William’s Orthopedic Center on Sixth Avenue, in the waiting room — alone, because my daughter is testing independence — I notice those adhesive arrows leading to the intake desk and remember when I was here last. It was decades ago — the fall of my first year of college — a time of my life polluted. I can still unquestionably remember the so-called “treatments” listed frivolously online as if they were inconsequential options at a fine-dining establishment. The PDF is somewhere on an old, lost flash drive.

We first saw it amongst typical, benign flyers on the dorm corkboard: “In need of one more player for our co-ed intramural soccer team,” “Dungeons and Dragons Cosplay Night,” “Red Cross Blood Drive,” and “Going Gluten-Free? Enroll in Introduction to Nutrition.”

My dorm mates, Hunter and Maxine, and I were shocked. I kept my internal questioning to myself: Do you have to be suicidal to partake? Would there be an entry and/or exit evaluation? Was the process confidential? Was there a limit?

Most importantly, could there really be a “cure” for suicide?

Maxine was already pulling up a Google search. Hunter and I guided her to a chair in our dorm’s antiquated lobby. Every fabric had its unique and aged smell: the fading green nylon carpet, the plaid sponge seat covers, the heavy and stained light-blocking linen folds of the white curtains, and the cracked paper lampshades.

The left half was dedicated to the mail room, RA office, supply closet, mailboxes, and unisex bathroom. The right half, the one we were currently huddled and whispering in despite being the only students there, was full of waiting-room-style chairs, loveseats, desk lamps, and side tables. The giant, multi-paned window watched us talk through the afternoon sun. The hills would soon block the sunset.

Hunter, the business major, pulled out his laptop from his bookbag. God forbid someone walked by and thought he was just on his smartphone, and not doing research. We browsed the Organization of National Psychiatric Therapies’ (ONPT) website silently.

According to the website, Suicide Simulation was not advertising it as a cure but rather an advanced therapy. To me, it didn’t seem like a bad idea, just one that shouldn’t be possible. Why the first location would be in southern Ohio was beyond me, although everyone does joke that Ohio is the worst state in which to reside.

Apparently, patients were encouraged to wear or do whatever they planned in their suicidal attempts or ideation. The ONPT, a mystery organization, encouraged patients to go through those steps before the appointment “to simulate the experience most accurately.” Not only could patients write letters and come wearing their prom dress or favorite band t-shirt, but they were also encouraged to get their families and friends involved. Whatever they’d do or planned to do in an actual attempt, they should emulate it leading up to and during the simulation.

I didn’t even try to understand the technology of it all. Hunter could only dumb it down to “a complex virtual reality headset.” Maxine, who always wore glasses despite having perfect vision, was almost emanating heat in her anger. I could understand Maxine’s reaction; she was four weeks deep into her psychology major and was already emotionally invested in her hypothetical patients.

I tried to draw a positive for Maxine. “Well, it does say patients go through an exit therapy session after the simulation.” I shifted in my seat. Older than me, it puffed out the smell of a thrift shop. I was worried I wasn’t looking at the simulation as critically as these two.

“I’m sure one therapy session could cure the trauma of attempted suicide,” Maxine responded. Of course, how could I have failed to see that?

Forever the financial analyst, Hunter reflected on how lucrative it could be. “The site says most insurances will cover the therapy. I bet they’d want to see a history of therapy, evidence of suicidal attempts, hospitalizations, and the like,” Hunter paused. “Regardless, it will be available to anyone who can afford it. Maybe ONPT will claim they need…” he searched for the word, “…‘nontraditional’ patients to help fund operation. Kinda seems like a pretense of therapy to me.”

“I’d think this would make suicide more, I don’t know, common? Feasible? Instead of thinking about universal therapy, affordable medication, mental-health leave,” Maxine hypothesized, “or just a general increase in the standard of living, we get this?” she threw her hands open wide.

I was in the middle of typical college student talk, albeit with a mind-boggling topic. My grandpa would mutter all the identifiers that had become tainted by modern media and political parties divided: Socialists! Liberals! Communists! Snowflakes! I could admit I’d seen the same transformation in my older brother when he visited home from college. But everything we’d learned so far was as equally eye-opening as it was gut-wrenching — the pink tax, redlining, food deserts, gerrymandering, greenwashing, the one percent.

I remember zoning out of the conversation, sitting there with my mouth agape and glazing over the expanse of mismatched chairs and side tables. At this moment, Maxine and Hunter were probably not remembering the secrets I’d shared about my family history under the comfort of a late night. Maybe they would only remember years later; oh my god, I totally forgot she had …

A mother with bipolar depression. I had found and read drafts of my sister’s suicide notes. The indecisive threat of it lived in the pale threads of angry skin jutting across her wrists. With all that, there was no room left for my mental terrors.

I couldn’t admit to Maxine and Hunter — the two with confidently selected majors alongside my half-hearted eyes closed, running my fingers down the undergraduate degree list and stopping on communications — that the simulation sounded like a genuine attempt. How did we know, profits or not, it couldn’t work?

Saving the nearing uncomfortable silence, Hunter made Maxine and I jump, “And what do they plan to do when this does fail? Money, resources, time … all wasted! They’re not trying to solve the problem; they’re just making money off the performance of trying to solve the problem!” He cushioned “solve” with aggressive air quotes. He was doing that a lot lately. Along with using “they.” Better than saying “the man,” I guessed.

“Or it’ll keep going. DUI Simulation. Start getting drunk drivers to go through an intoxicated car crash.” I remembered the “Overdose Package” from that grotesque menu. “Have drug users experience a fatal OD? Jail Simulation?” I fit my voice into a deeper container, “Considering a minor crime or petty theft? Think again after our new and improved Jail Simulation!”

“They’d never go for that. The type of people that resort to petty crime are not their clientele. Plus, you’d be asking the Simulation to solve the wage gap, not cure a shopaholic,” Hunter rationalized.

He did have a point, but I finally had something thoughtful to say. I couldn’t fathom the difficulty in trying to simulate the complexity of an overdose. How could you simulate that? Where the person overdosing typically isn’t aware they were overdosing. Instead, riding the high, they experience their brain releasing dopamine in quantities it had never previously allowed. By the time they were foaming at the mouth or choking on their own saliva and bile, their brain was on its way to being dead. Their body temperature low, their heart either overly-enthusiastic or barely moving even with the poke of a defibrillator.

Would the simulation end with the flooding of Narcan or a brash reprimanding? Instead of the best high of your life being the end of it, you woke to a plastic surgeon-turned-therapist telling you now that you’d had your cake, you wouldn’t want to eat it too.

And still …

We remained huddled for a while. Indignation filled the room with nowhere to go.

When Maxine and I returned to our dorm room, she said with a laugh but questionable humor, “I wonder if presenting my University ID will get me a discount like at Goodwill or Bob Evans …” I didn’t know how to respond. I couldn’t tell if she was more interested than upset. Or, if I was projecting.

***

My interest noticeably shifted as Maxine and Hunter drifted towards parties, new friends, sex. The Suicide Simulation consumed the news less and less, but I always got the latest, going against my better judgment and setting up alerts on my phone. Like in high school, parties and boys didn’t mix with me. When I attempted to partake, I puked from a few sips of alcohol or drooled out of my mouth, anticipating a kiss.

I couldn’t help myself. I couldn’t stop talking about it. I was more obsessive than in my Vampire Diaries or K-pop phases. From then on, there was a shift in our lives and our conversations, at least on my end. The aggravated updates took priority over my social life, school, and responsibilities. Homework breaks always fell to internalized discussion panels, walks around campus became imagined Ted Talks and movie nights were distracted by my obsession.

I stopped getting invited to parties and dorm-wide events, although I wasn’t ever a first pick. Everyone stopped asking me for help with homework or studying. Maxine and I stopped sharing clothes, and I suspected she and Hunter might have been hooking up as if I’d care or intervene if I knew their “secret.” This device took all of my attention, and I was so limp around boys that I couldn’t possibly form a type. Maxine could have Hunter and keep her vintage denim.

Meanwhile, I was ignoring phone calls from my mom, occasionally sending her articles against helicopter parenting your college student, why single parents should still maintain some semblance of hands-off parenting, and “When’s the Best Time to Resume Communication with Your First-Year College Student?” I came to appreciate the parenting blogs my mother had used against me in the past. She’d bite back with something related to young adult mental health statistics, all the while ignoring keywords like, “generational,” “breaking the cycle,” and “respecting boundaries.”

If I ever mentioned an interest, a contemplation, in Suicide Simulation, she’d somehow find a way to institutionalize me. I was there for her reaction to my sister’s notes. I wasn’t letting that happen to me. And it was so frustrating to see her advertise the benefits of therapy, medication, and even hospitalization but never as options for herself.

Still, I wondered if any of it would have kept the bottle of pills from her mind. I wondered if my sister would see her wrists as evidence of her delicate, meaningful purpose here and not as escape mechanisms. I wondered if Suicide Simulation could throw a wrench in the generational gears of hopelessness. I wondered if a pilot light of hope was within me, ready to be ignited by some outside force.

A few more weeks into our semester and a few weeks after the release of Suicide Simulation, the complications began to show themselves. The issues were plentiful. First came the wealthy adrenaline chasers and expensive curiosity. Maxine and Hunter, who would still swing by to scream anarchy now and again, said, “I knew it.”

We were in Maxine’s and my dorm room, white twinkle lights adorned the ceiling, and the movie, The Princess Bride, paused just twenty-seven minutes in. Our eating habits worsened with the depth of the semester and the stress of these new, expected and unexpected parts of life. In the midst of the blankets, pillows, and chargers were Funyuns, Grippo’s potato chips, extra-buttery popcorn, gummy bears, cosmic brownies, Mountain Dew, store-bought buckeyes, and caramels. Maxine called them emotional-support calories. We laughed, and I wondered if the three of us would even be here together if it weren’t for this box of a dorm room to which Maxine and I were assigned.

Maxine brought up Suicide Simulation less and less, but Hunter would latch on when she did, trying to impress her and stroke his ego.

Hunter spoke between bites of gummy bears, the handful of colors mixing in his mouth, “Then there’s the masochists. Some of them, I’m assuming, already knew they were …” Watching Hunter’s numbers brain try to come up with the right words was funny. “… Sexually satisfied by, yeah.” He ate another handful of junk. “There’s rumors of medical staff turning a blind eye to patients using the simulation for other purposes …”

“There’s no way you’d get away with that. It’s not a sperm bank!” I couldn’t picture a nurse casually turning their back to moans of pleasure. Still, Hunter and Maxine looked at me like my lack of sexual—let alone social—activity made me too innocent to believe it.

“There’s always some truth to rumors, though, right?” Hunter asked.

Maxine felt obliged to advocate for the patient. “I know all of these crazy stories are ridiculous, but what about the actual patients? I would feel so embarrassed; I don’t think I could go even if I needed or wanted to. Seeing people post a selfie in front of the Suicide Simulation sign or share the location on social media. It’s like, you are the reason they invented this, but you’re not who they want using it. The people this is meant to help are completely ostracized.” Maxine and I were both guilty of throwing around college-level vocabulary we’d just learned, like ostracism or hubris.

“Right. I think about that, too. Imagine the patients waiting in line next to the spoiled rich people taking the simulation for spin after spin.” I pictured my sister and how it all started when she wasn’t even a teenager, before all of her adult teeth were in. “Like, children — children struggle with suicide and all of that. What do they do?” As usual, we took a moment to sit with it all. I sighed, looking at the time and realizing it’d be another late night, regardless of when Hunter left. I’d be worrying about my sister, thinking about how so many things weren’t enough to keep her here. How, as selfish as it was, she’d leave me. I don’t know how much of me would be left without her.

Maxine pressed play on the movie, and we dived into our snacks. It was difficult to hold back more comments over “As you wish,” and “Inconceivable!” The simple comforts of my youth were losing their effects, and it seemed maybe I was beginning to understand my sister’s belief that she had seen all she needed to see at such a young age. She was fully aware of what she’d be missing and, frankly, didn’t want any of it.

Yet, each week brought our weakening triumvirate more sour news from anonymous inside sources. Exposing what ONPT called, “minor, expected hiccups.” There were claims of patients of all kinds returning again and again. It seemed clear they were uncomfortably addicted. Of course, since Suicide Simulation was dubbed an “alternative therapy,” patients were encouraged to frequent as much as needed.

So, I couldn’t find the energy to accept Maxine’s half-hearted invite to join her and Hunter at a favorite coffee shop. Instead, I huddled in my bed and let my thoughts go deeper and darker. Having cycled through different therapies and therapists, I could see I was on the wrong half of my peak. I’d moved out, started college, found a little bit of myself, and now I was staying in my dorm with the blinds closed, watching meaningless reality TV on my laptop because I couldn’t be bothered to get the remote for my little flat screen. I wasn’t getting enough sunlight, socializing, or exercise. My sleeping and eating schedules were off. My inner monologue was full of self-pity and self-loathing—“negative self-talk.” I was intimately aware that I was letting myself fall into another low point.

In the light of my laptop, I’d read that ONTP began limiting the number of treatments one could take a week — fearing some patients would never see the treatment at this rate. One doesn’t have to be an adrenaline seeker to crave the indescribable sensation of escaping through death. I remembered what it was like to almost get run over by an ATV and walk away feeling like the me before near-death had died, and I had this real, authentic purpose in a body that was finally awake and aware. The purpose of living is as simple as wanting to live because you don’t want to die. But it lasts as long as a mosquito bite and is as easily forgotten as milk on a grocery list.

Having such a grand display of treatment had many — mostly influencers, celebrities, and the wealthy — much more open about getting treatment. How sweet of them to publicly unburden the trauma of being asked to do another commercial for triple-antibiotic ointment. Maybe we, those who remained quiet, didn’t talk about our problems because we feared appearing weak, believed to be somehow less than. But maybe, and more likely, those who were quiet and hidden were quiet and hidden because no one listened to their language. Beautiful people in beautiful clothes with beautiful backdrops telling the rest of us that we’re warriors, warriors living paycheck to paycheck who can’t afford an international phone call, let alone a Telehealth therapy appointment. These were the people who were often spoken for, spoken over. So why talk when there was no room for us? Why come out in the first place?

I saw it in my own flashback with my mother. We were driving home in the dark. Maybe it was actually dark at the time, or my memory saw the context and emotion and thought it would be fitting to be dark. Regardless, I don’t remember the day or what happened when we got home. But, driving home in the dark, I was crying. My mother’s voice was sharp and tiptoeing frenzied.

“I don’t know what you want. What do you want? What can I do about it?” She interrogated.

Through tears, I said what I remembered repeating often that night but never again, “I just want you to listen. Just listen to me. Can’t you just listen to what I am saying?”

“But what do you want me to do? I can’t fix everything. I have to fix everything, and sometimes I can’t!” She had set the cycle in motion again.

I felt myself actually squirming in frustration, overfilling the passenger seat. I couldn’t be more clear. “Just listen. I want you to listen to what I’m saying. Just hear what I am telling you!” But, the car ride continued with the vehicle going forward and us staying very much in the same place. I never tried again with my mom. She couldn’t hear me because it’d mean she would have to admit that she couldn’t fix it — that I couldn’t be fixed. Maybe it’d trigger another depressive episode, maybe what I kept inside would do more harm outside, so it stayed within me. I kept it all in. The fear that I would never be good enough, which had me wondering what was the point anyway. The concern that maybe I was becoming more and more like my sister.

The story broke a month or so after the big grand opening of Suicide Simulation.

“The defense team for Quintin Romero is trying to have it ruled as involuntary manslaughter,” I read-whispered over the pseudo-wood table in the stacks of pungent library book covers and pages.

I researched with the confidence and speed of an unconvincing hacker found on NCIS. I needed to read more. What popped up was a mother’s plea. What I remember to this day:

After Suicide Simulation, my son was worse off. He didn’t say anything, but we saw the change. Even if I hadn’t found the note that said he wasn’t scared anymore, I’d know it was that simulation. As parents, we were hesitant, but he wanted to be done with medication and therapy. He thought he could finally be free …

I was so engrossed that I hadn’t noticed my tears until I’d scrolled down to the end of the article and into the advertisements — weight loss pills, local and hot singles, and which Friends character are you? Clickbait.

Of course, ONPT had their PR team at the ready with a statement posted on every page of their website.

***

That evening, at the party everyone surely regretted I’d overheard the invite for, I spread the news better than any local blondie in front of the ABC Station.

“Total bullshit,” I huffed. “They’re using his death to make more business. Claiming that they are not at fault because of the nature of their work, of their patients!” I was irritable and confused. But I had to try to speak Maxine and Hunter’s language. I wanted them to react. I wanted to talk about the simulation. I still wanted to believe in the simulation.

No one reacted, but I spoke to whoever had the misfortune of standing near me. Hunter’s group project partners that he’d practically deified. Maxine’s friends visiting from “home,” an entire forty-five minutes away. “I still cannot believe they did not see this coming,” I fumed. “They had to see this coming. Everything we learn” — as in my frenzied researching skills — “about suicide prevention tells us to distance the patients from suicidal ideation. Instead, encourage social buffers, reminding them that the people in their life — friends and family, coworkers, strangers even — are there for them, care for them. Implementing long-term, lasting measures: talk therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, collaborative assessment, management of suicidality, lasting coping mechanisms, and medication. Remove feelings of burdensomeness and hopelessness. Identify the individual’s unique risk status and risk factors …”

I started sounding like a Mayo Clinic treatment chatbot, and I probably understood what I was ranting about as much as a bot. Obsessing about it on my own, I had tried picking up Hunter’s financial and Maxine’s psych slack.

“Like this week, I learned about habituation. It’s one of the major factors that make the capability for suicide more plausible, I guess, more realistic. The more the suicidal individual experiences pain, injury, fear, and exposure to death, the more likely they are to act fatally.” No one was connecting my dots. Maxine’s friends were probably calculating if one of them was still within the realm of sobriety to drive home; Hunter’s crew didn’t have to pretend to look disinterested. It seemed to be their constant state. And Maxine and Hunter were too over it to bite.

Still, I persisted. “So, basically, the person gets used to the idea of dying, they think: ‘I’m not afraid to die.’”

Maxine pushed her glasses up her nose as if needing them to see and think clearly. She kept opening and closing her mouth to say something. Hunter was more upfront. “Christ,” Hunter breathed. Finally, someone was getting it. I looked at him with the rest of the group, nodding him on.

“Can we not talk about this tonight? God. It’s bad enough we have to see it on the news; you don’t need to be the parrot. It’s like you want to try it or something. Move on. Better yet, try it for real, for Christ’s sake! Just stop bringing us all down with you. Fuck!” Hunter didn’t stick around for a response, crushing his beer and heading inside, and I didn’t blame him. I could hear myself, but I couldn’t stop.

I turned to Maxine, “Maxine, I’m sorry —”

“Listen, that was harsh.” Maxine interrupted. “But it’s true. You gotta stop with this.” By now, the rest of the party had moved from the front porch to inside the dilapidated, chipping house. “You were my first friend here, but now, you’re…unbearable if I’m being honest. It’s all you talk about. It’s all you think about. We can’t change anything, you know that, right? We have no control over what they decide tomorrow. We have no control if anyone dies. And, honestly, I can’t control that I don’t care about this. It sounds heartless, but I can’t let my life be influenced by every little thing I hear on the news. There are wars over oil, animal testing, and sex trafficking. And I still have to wake up daily and live my life.” She gave me a look. “You should, too.”

How could I get Maxine to believe that I knew all of this? That it didn’t matter anyway.

“I —”

“Do you, like, think maybe you need to talk to someone? You know, someone who can help. Not someone who tells you to off yourself.” Maxine would be the one to call out Hunter, just not in front of him.

“Really, the best help I think I need right now is my friends back. I’m up in my head all day, every day.”

“Ok, Hunter and I will work on that. But, seriously, you gotta check yourself a little bit. Maybe talk to your mom for once.” My face shifted at her approach. “Or a therapist. But we can’t take the brunt of it. Friends can only do so much.”

“Yeah, for sure. But, I’m gonna head out. I’ve kind of ruined the party.”

“No, stay. We can play beer pong. We just need —”

“It’s okay. I don’t want to be awkward. I’ll see you back at the dorm.”

To no one’s surprise, our friendship didn’t get any better from this point. I still couldn’t break from my obsession, and Hunter and Maxine started officially dating. She stayed most nights in his dorm anyway. I told myself I would’ve been a third wheel regardless, a temporary donut until they found some better tires.

My college experience was robotic. I went through the motions, tried therapy, again, and accomplished what I was expected to achieve. I barely made it through a simple Communications degree. I still felt like I didn’t know how to live with myself, like I was an unwanted side-effect of the real purpose of my life. I did what was predictable, expected, so I was not pushed into something unpredictable. I became what the girl who moved into her dorm room with hope and a million versions of plastic drawers hoped to avoid.

And I never told Maxine and Hunter I had tried it. That would require an explanation for which I had no words.

The day I walked into that building, I had never sweat so much in my life. On the ride over, I had removed my shirt to save it from the onion and sea-breeze odor. After putting the shirt back on, the armpits cold, I took note of the cars on the newly paved lot. The vehicular assets that cost more than my life. Lincoln, Mercedes, Mercedes, Cadillac, Ferrari, Lincoln, Corvette. Already, I felt uncomfortable stepping out of my Honda Civic with a large portion of my savings in hand.

It didn’t matter. I couldn’t ignore the tether yanking me through the sleek silver doors, pulling me towards something outside myself to try to salvage what was within. The doors were heavy and difficult to pull open enough to fit through. As instructed in the voicemail, I went to the left secretary’s desk. The right, I was told, was for emergency walk-ins. Emergency how?

“Good afternoon,” said the model secretary. “Can I have your last name and verification pin?” She showed me her bleached teeth, and I got the impression she wore glasses for the same reason Maxine did.

“Uh, yeah. It’s Farell and 6-7-2-9.”

“Thank you. It looks like you’re here a little early.” Yeah, you guys told me to come half an hour early. “So, follow the red arrows — see them?” I nodded. I could see. “Follow those to the waiting room. When they’re ready for you, a nurse will get you.”

Annoyed, I followed the red arrows intermixed with an array of other colors. What possible purposes could orange, purple, or blue have in a place like this? The waiting room was as expected. I browsed the literature on the side table next to my stiff chair. I read a few lines as I waited. Thirty minutes became forty-five, and my embarrassment at being there hid behind my frustration with the extended, unending wait. I didn’t want to think this through anymore. Nor did I want to be caught here.

When a nurse finally hailed me, we walked to an elevator and took it to level four. There were no labels on anything, not even a name for the floor we were on. No signs at main desks, on doors, or cabinets. Just arrows. We went through a common set of double doors, and she took me to a room on the left. The room looked similar to a family doctor’s office, except for the large contraption hovering above the head-end of the examination table. I’d say it looked like an MRI machine — had I ever seen one in person — or a modern guillotine — if that existed.

My sweating had picked up again. My heart was the loudest machine in the room. I was unforgettably nervous, watching the doctor and some tech guy come in and begin setting up as the nurse connected me with sensors and tubes. None of them spoke during this, trapping me in my head.

Sitting there, I realized the room was too cold and too sterile. My open toes in flip flops and my cotton t-shirt were fighting the sixty-five-degree, fully tiled, startling white room. The room smelled too strongly of bleach, and there was nothing to look at. There were no strange charts of how the brain works or pictures of happy parents with a happy child sitting on lush, green grass. Just white walls and a room of medical experts who didn’t seem to have the bedside manner training for a situation like this.

When the time came, the doctor read my vitals aloud, showed me the button in my hand that could stop the simulation when clicked twice, and asked if I was ready. I nodded. He asked if I could verbally confirm; I said yes.

“Ok, Ms. Farell, the simulation is about to begin. We will be right here if you need anything. We will be in this room the entire time. I will manage your dosages, nurse Angela will monitor your vitals, and Joe will monitor the simulation through this screen.” A pause. “Let’s begin.”

He strapped the headset over my face, and immediately, the machine came to life. It was believable. Frightening.

I was in my dorm room, stolen somehow from my consciousness. Recreated poorly: the rug was red and cream, not blue and cream; the curtains were sheer white, not thick white; the overhead light was not painfully bright enough; Maxine’s bed was made, not unmade. I wanted to explore the drawers and closets and investigate the feel of my bed. It felt like I was a doll version of myself, my mind acting as the hand of what would be the child maneuvering me. I reminded myself there was surveillance in what felt like my mind, that the tech guy was watching me.

I walked over to my university standard desk, seeing the optional pen and paper. I considered the paper; it was thick, made from the pulp of raw materials sieved and hard-pressed into this expensive paper speckled with flecks of lavender and leaf confetti. I’d never own paper like this. I don’t think I’d ever leave a note, either. What would be worse: never enough last words or no words at all?

Next to the note was a gun. Modern, sleek. Deadly — simulated deadly. I didn’t know what else to pick, and it was the cheapest package.

Common?

Quick?

I picked it up, heavier than expected, and I didn’t know how to use it. The IT guy must have placed the prop in my hand, because I was genuinely holding something. I stood in my simulation, looking around with a gun in my limp, insecure hand. A voice came over an invisible speaker. Well, to my ear. “Ms. Farell, the safety is off. So, pull the top of the gun back until you hear a click. That means it is cocked. Then the trigger is ready to be pressed, releasing the bullet.”

“Oh,” I said in the simulation, and out loud I guessed, “thanks.” No response. I wonder if this tech guy ever imagined he’d explain to a depressed college gal how to shoot herself in the head. This all felt too gross. The room became more convincing the longer I was in the simulation.

Before the simulation started, I knew it was visual trickery, but now that I was here, I felt like I could live in this little world. What if I hijacked this simulation and built friends like Sims characters? I could pretend the glitches were just ticks. I would get used to the constant smell of cleaner. I could turn up the heat in the room. I would finally hang up that dumb “Make Love Not War” poster I bought at the local overpriced thrift shop.

I went and sat on my bed. I looked at the gun in my hands, the only time I’d ever interacted with one. I took a deep breath; I was crying, but felt only dryness on my face in the simulation. It felt wrong. It was too late. I was here.

It was as unreal as it was real. It was the same as scrolling online for hours, acting like it was a natural part of life. Would any of this compute in the real world? Would I even be convinced?

I wanted out.

I pulled the top of the gun back, hearing the click.

After, I was told the whole experience lasted four minutes. It took fifteen minutes to come to. Fifteen minutes I can’t remember. To this day, I wonder if my unconsciousness knew it was still alive. When I did jolt awake, my forgotten scream returned. The nurse calmed me and reminded me where I was and what I did even though I knew. I’ll never forget.

The exit therapy session was meaningless, forgettable, and more like a guided questionnaire. I hovered above my body as it walked out of the structure. Still, I hover, like a ghost.

After, my life felt like it was walking around holding a secret. I felt like a symbol, waiting for someone to notice. Was I cured? Did I now brush my teeth to preserve my health or because I didn’t want someone to have a reason to stare at my teeth? Did I feel honest love for my life all of a sudden? Was I even depressed? Or was there just some emotional switch in me that was broken? Was my curiosity appeased? I still wasn’t sure I understood why I went and if I was ever a real candidate.

The truth is, I feel like maybe we all walk around thinking if a car came at us, we might stay in its way if it weren’t for adrenaline, instinct, self-preservation. But who was watching? Who would see? There are millions of cars and billions of people, and we are trained to say “yes” and “no.” And I wish I hadn’t said either.

I never told my daughter about it, never perverted it into a sob story, a life lesson like my mother would have. I will admit, though, my mother is a much better grandmother. But I can never get myself to lecture my daughter. To make her feel like I know anything more than she does because I don’t. I can’t explain to her how time works and how much you waste wishing things were different.

A while after my suicide simulation, a chronically depressed sixty-two-year-old patient experienced a “cardiac event.” Dying right inside that death simulation. His wife had said, in drooled and sniffled stutters, that “he had tried everything his entire life.”

She hoped this was not what he wanted. That he was so terrified of the simulation of leaving her, her living without him, that his body overreacted. That the thoughts that came to his mind were only of living. Maybe I am misspeaking, but I imagine that was something like what she was thinking. What had gotten her to bed every night since?

The Simulation was shut down immediately after the man was carted out, draped in the white sheet of pure, overdue vindication. To this day, this experiment, Suicide Simulation, remains closed. The structure has since been outfitted into this orthopedic center. Maxine was right. The building remains. Depression remains, and suicide remains. The arrows remain. We remain.

The Simulation was destined to fail, much like its patients in the world it was designed in.

I can’t say if the Simulation changed me. I don’t know if it was that I saw life differently after or if life just became different for me in the way it does for anyone entering adulthood. Life takes on new meanings, and maybe it’s not so much choosing and fighting for life anymore. I don’t think we have the time to think about living. We just do.

We will never have the answer or solution. I’m not sure we will ever have the rationale either. Some people love the color blue, others green. Some people choose to live, others don’t. Even with our greatest technologies and our best advancements, I’m not sure we will ever truly understand why that is.

And so, again, we crawled back to our hiding, looking over our shoulders one last time to ensure no one followed us into the dark.