For the first time after nearly half a century, I finally returned to Songzi, my native town located close to the Yangtze River, where I decided to spend a whole week trying to fulfill my growing nostalgic needs.

After doing much detective work, I found Yao, my oldest friend, who was said to have fallen mentally ill in his mid-thirties, and invited him for a dinner party at Du, a famous local restaurant. Early in the evening of October 15, he showed up both in good time and in good spirits together with Bao, our mutual friend, a musical teacher at Songzi Old Age College.

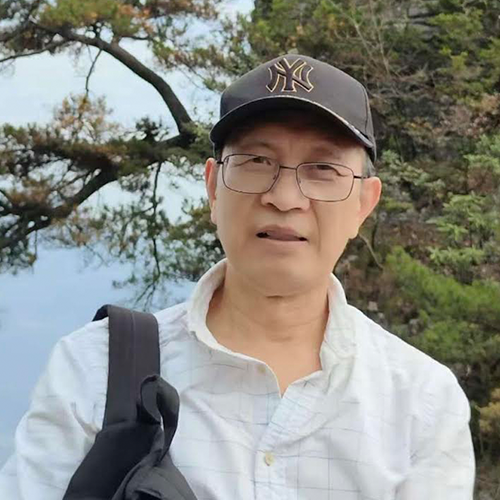

Lean, white-haired, Yao walked towards me with a cane in his left hand. “So, you’re really Ming?” he said, his eyes sparkling with wonder. “Long, long time no see!”

“When did we see each other last time?” Bao chimed in.

“Fifty-one years ago,” I replied.

Sitting down around the table, we began by recalling our childhood pranks. To Bao, the most memorable experience we three shared was the snake episode, which created a big stir on campus when we were eleventh graders. As the best slingshot hitman of the whole school, Bao killed a long black snake, which I skinned and cooked in my home. Yao swallowed its spleen supposedly to make his eyes sharper; I bloated the intact skin into a stuffed snake and later put it randomly in a different classroom on a different school day.

The moment the main course, called Du Family Rooster, a hotpot of a whole rooster fried and stewed with a lot of rapeseed oil and chillies, was put on the table, I stood up and told them both to dig in. When I mentioned how I had tried to beat Yao in our second year in elementary school by bragging about my father (who was his father’s inferior in the county government), he laughed good-naturedly at my foolishness and went on to remind me how I once flexed my hillbilly hairstyle a few years later when I returned to the town from a village school.

To him, the most important part of our high school life was our young ambitions. He remembered well how I had longed to become a poet, Bao a musician, and he himself a Chinese Van Gogh. Knowing that Bao had realized his boyish dream and I had become the most widely published author of English poetry from contemporary China, Yao told us proudly that he had produced more than 50 books in addition to thousands of paintings, though neither a single page of words nor a single picture had ever appeared anywhere except in his own dwelling place.

From Bao, I had learned that Yao started as a highly promising aircraft engineer in a major state-owned enterprise after graduation from Nanjing Aeronautical University, married a very talented woman after a romantic encounter on a cruise, and won a lot of prizes for his artwork before his mind went astray and he had to resign from his job.

“How did you return to Songzi to live all by yourself?” I asked.

“I had a car accident and broke my ankle permanently,” Yao answered, in a calm and matter-of-fact voice.

“When and why did his wife and daughter leave him?” I asked Bao in a low voice, who answered my question simply by saying, “She disappeared once and for all without even going through a divorce soon after the accident.”

“I don’t remember having a wife or daughter,” Yao barged in, apparently having overheard our conversation. “All I know is my paintings are as good as Van Gogh’s.”

Yao was still living in his adolescent dream despite his old age, I said to myself, remembering how passionately he used to talk about his artistic pursuits, and how determined he had been to emulate his Dutch mentor.

“It’s good of you to stay gold, dude,” I told Yao in a sincere and appreciative tone. “Will you give me your best writings so I can publish a few books for you?” I offered. Since I had a small press of my own in Vancouver and a lot of editorial and publishing experience, this was the least I could do for my oldest friend.

“The problem is, all my writing is casual,” Yao explained. “I’ve never got any time to edit them.”

“What’re they mainly about?”

“He has written on every topic, ranging from specific historical studies, art criticism, cultural observations and folklore to contemporary politics and international relations,” Bao told me on Yao’s behalf.

“How about compiling your best writings into a quotation book?” I suggested.

“Nah. I just want to concentrate on writing,” Yao replied. “Most important, though, I want to paint a lot more and better pictures than Van Gogh did. After I die, people will recognize me and collect my artwork.”

To me, Yao seemed as clear-minded as Bao and myself. But how come people keep saying that he’s a lunatic homebody who’s been suffering from severe mental disorders? From his demeanor, he is obviously able to think logically, speak intelligently, and move around properly. He tends to show too much enthusiasm and take too much pride in his creations when it comes to fine arts or literary writing, as Bao has told me before, but isn’t that characteristic of any “normal” artist?

When we finished our dinner, I asked Bao to send Yao back to his spacious condo unit, bought by the latter’s younger brother, who had just retired as Head of Hubei Provincial Department of Health.

“Farewell, dudes,” I said to both of them. “I’ll see you when I see you!”

“I’m in it with all my heart!” Yao said, sounding as devoted to his art as Van Gogh himself, though a bit out of tune.