Wooden pieces of a futon frame are spread out on the floor in a disorderly fashion, waiting to be assembled. Discarded in a corner of the bachelor apartment is the cardboard box they came in. Jerry is standing at the kitchenette counter using your new phone, the receiver cradled under his chin. One hand holds open the phone book as the index finger of the other pushes the phone’s buttons.

The futon mattress is still rolled up in its plastic sheath and bound with coarse twine at either end. You sit on it, as if on a log, looking over an instruction booklet and checking every now and then to see if all the boards, slats and pegs on the floor correspond with what is in the booklet. Jerry is ordering a pizza. You empty a bag of metal screws, bolts, washers, nuts and an Allen key on the floor (rechecking the booklet to see if everything is there) when you hear Jerry tell whoever is on the other end to also bring a six-pack of Bud.

You’ve had the phone since yesterday. Mr. Childers let you take part of the morning off to pick it up at the phone company, as long as you made up the time by working through your lunch hour and afternoon break. What’s moving around a few extra drums? The apartment came with a jack-in-the-wall by the kitchenette. When you got home and plugged the phone in and heard that dial tone, it felt like a small victory in this new phase of your life. That steady drone was the official start of this period of starting over.

Now you can’t help thinking that the first call being made is to order beer. You look up at Jerry, knowing you should say something, then look down helplessly at all these pieces of the disassembled frame as if they are parts of a puzzle you know in your heart won’t fit together.

After giving the address, Jerry hangs up the phone and walks around the pieces of wooden frame. He seems to be taking silent inventory.

-Don’t worry, he says and rubs his hands together.

-We’ll have this baby put together before the pizza gets here.

-Did I hear you order beer?

-Yeah, that’s why I called Benito’s. They know me and they’re cool about delivering beer as long as you order food.

Jerry frowns as he clues into something in your expression.

-Oh, shit. I’m sorry, Marty. I wasn’t thinking. I’ll call them back.

-No, it’s cool. As long as you’re prepared to drink all of them.

You feel better now that you’ve spoken up and laugh. It’s no big deal. Jerry offers to pay for the beer.

-Don’t be silly, man. I appreciate you driving me to get the futon and helping me carry it up here. The least I can do is buy you beer and pizza. Really, don’t sweat it.

-Okay. If you’re sure. I can call them back and order some Cokes for you.

-I think I’ve got some in the fridge.

Maybe you shouldn’t have said anything.

-I don’t have to drink them here. I can put them in the car and bring them home.

-No, don’t be crazy. I only mentioned it, you know. So that you understand I can’t join you. That’s all. You can drink in front of me. It’ll be okay, really.

True to his word, Jerry takes charge of putting all the boards and slats together while you assist. In half an hour they are fully assembled with the futon unrolled and fitting perfectly on the frame. Jerry demonstrates how half of it can be moved up until the wooden pegs click into place so that it is now a sofa with the sunny charm of a salesman in a showroom.

-See? One minute you’re in your living room and then with just a push and a click, it’s bedtime. Jerry straightens the frame flat out again.

-Just the thing if you’re entertaining a lady friend, let’s say, and things look promising.

-I like the way you think. You lift the back of the frame so it is a sofa once more, pleased with how easily it converts.

-But it’s probably best not to get ahead of myself for the time being.

You really are grateful, knowing it would most likely have taken you much of the day to figure out how to put the thing together. Building things or working with your hands, in general, was never your strong suit. The fact that you got a blue-collar job, after years of wearing a suit, still strikes you as funny.

In a couple of minutes, the pizza arrives. You pay the delivery guy and give him a good tip. Jerry takes the six-pack.

-I can put these in the car. I’ll just be a sec.

-What are you talking about? I think you’ve earned a beer.

Jerry stashes the six-pack in the fridge.

-Let me get some pizza in me first. I have to drive home.

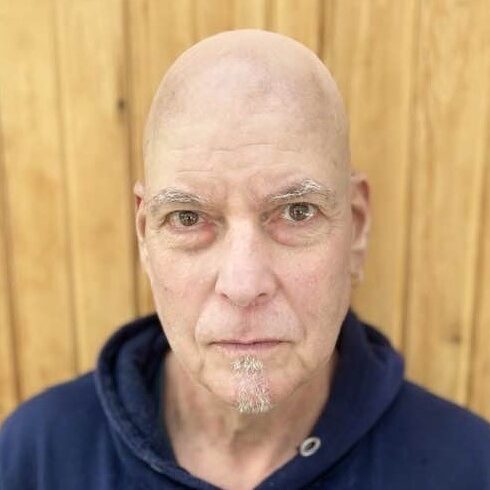

Jerry is someone you’ve only recently become friendly with at Ferguson Chemicals. You were still living at the Oasis Center when he started asking you about the book you sometimes read while eating lunch on the grass outside the loading dock. Trump: The Art of the Deal. You explained how you got it second-hand at a pawnshop (the same one where you bought the futon) when you went to hock your whiskey flask after you quit drinking.

In a way, the book has become a kind of talisman of your sobriety, the same way the flask had been when you were still drinking. After all, you’ve been making deals your whole life. Obviously with clients when you were a salesman but also with Roz and Dani. All those trade-offs that make up a marriage and being a parent. And now, a deal with yourself, here in Las Vegas. Half a year into recovery at age 51.

After each of us has a slice of pizza, you reassure Jerry that it’s no problem for him to have a beer.

-The thing is, I’ve been living in rehab for the past six months. They call it a halfway house and the whole time, it felt like I was living a halfway life. I don’t want this place to be an extension of that. Sure, I can’t drink. I don’t want to. But you go ahead. I just want to live a regular life. If I wanted to only be around people who aren’t allowed to drink, I’d have stayed at the Oasis Center.

It’s like what Trump wrote about using your leverage, not looking desperate or letting the other guy smell blood. Jerry gets a Bud from the fridge and twists the cap off. He takes a long swig and returns to the futon for more pizza. You feel good about seeing him drink the beer. You hope you’ve made him feel comfortable in your home. Rather than the gnawing resentment of not being able to have a beer too, you lean back on your fully assembled futon sofa and bask in that inexplicable tranquility of having the upper hand.

***

Sleep comes easily for the next few nights, more easily than it ever did at the Oasis Center where you and one other had to share that cubbyhole of a room. Instead of curling up on a narrow single bed, you have a spacious futon to stretch out on. No more waking up to someone snoring in his underwear and socks in the next bed over. You strip the blanket, sheets, and pillows from the futon and lift half of the frame into place so it is a sofa again. Starting off this way before you shower, dress, make coffee, or even light up your first smoke, establishes a much-needed structure to the day. Giving you a kind of leverage, a way to justify things to yourself.

Case in point, you have yet to go to a meeting. True, you promised Jonah you’d swing by the Center and you have every intention of doing so. He warned you about cutting ties too quickly—the danger of thinking you can go at it alone. In his five years as director of the Oasis Center, he’s seen it happen too many times.

But you want to be able to tell all the other residents still living there, without a doubt, that you are making it on the outside. Standing on your own once more. Too many expectant faces would be sitting there nodding sympathetically but also waiting for you to fall on your face and come running back. Would you tell them about Jerry ordering beer with the pizza?

Watching him drink the first one was easy enough. You play it over in your head at the kitchenette counter with that first cigarette and sip of morning coffee (milk and four sugars or “the recovery regular” as some of the guys at the Center call it). You can’t help re-enacting your sidelong glance, as if he’s still there tipping back his head with his Adam’s apple bobbing, while you butter a slice of toast and peel a hard-boiled egg. But the prospect of Jerry having a second beer led to an unexpected grey area.

It was getting on to late afternoon. Jerry kept saying he should get home. He and his wife were having a date night. She found a sitter for the kids and he had to take a shower.

-Thanks again for all your help. I’d probably still be trying to figure out how to put this thing together.

-In a way you’re lucky. I mean, I know it probably hasn’t been easy for you. But you’re getting to start over. Kind of wiping the slate clean, I guess. That must be hard in a way but I’ll bet a part of you feels good too.

You nodded, not knowing how else to respond. Without thinking you got up and went to the fridge. Even as you felt the coolness and the weight of the bottle in your hand, some instinctive sense of propriety told you not to twist off the cap. You brought the beer to Jerry and he took it, his only form of thanks being a slight nod. This was not the usual social exchange of host and guest or alcohol-fueled male camaraderie. This was a tacit agreement. Not as clear-cut as mutual vicariousness, although there certainly must have been an element of that (on your part anyway, but maybe on Jerry’s too).

The absence of words allowed any questions of guilt or shame to be subverted, or at the very least sidestepped. One might go so far as to say Jerry untwisted the bottle cap in a compliant manner. He drank this second beer slower than the first one. With the first one, it was a matter of washing down the pizza he’d eaten. But now he didn’t want any more pizza, since he was taking his wife out for dinner.

The second beer was an entity unto itself, a point of reference. The moment the last dregs slid down his throat, he handed you the empty bottle and got to his feet.

-See you at work, he said.

-Sure thing. Thanks again.

You stood there turning the empty bottle in your hands as Jerry retrieved the other four beers from the fridge and left the apartment. Whether this marked an ending to your friendship as it was or the beginning of something else remains unclear to you.

You look for clues in Jerry’s demeanor at work. You ask how date night with his wife went. He jokes that he got lucky. He asks how you’re liking the futon. You assure him you haven’t got lucky yet, but you’re sleeping like a baby, then casually mention that there is a card table you are thinking of buying at the same hock shop where you bought the futon. It comes with a couple of folding chairs. Something you can sit at for a meal so you don’t have to stand to eat at the kitchenette counter.

Jerry smiles and nods but doesn’t offer to drive you to pick them up and bring them back to your place. The disappointment passes. You both get on with your work.

Maybe he thought you already had a way of getting the table and chairs from the hock shop to your place? Maybe he expected you to ask him outright? The last time he made the offer to help was because he overheard you telling Mr. Childers about the futon and wondering how you’d get it home. But you know something is different this time around, the way he smiled and nodded. It’s that unspoken thing. Not exactly the same as when you got him that second beer. Then he merely twisted the cap off and drank it slowly, as if to say what the hell. This time, the smile and nod sent a different message, the more you think about it.

***

Growing embarrassment soon gives way to resentment and then defensiveness. It’s not like you forced the beer on him. After all, he was the one who had them delivered in the first place. It’s not like you twisted the cap off so he had to drink it. You didn’t do anything wrong. He can smile and nod all he wants.

Then again it could all be a misunderstanding, on your part and on his. Maybe you need to say something. Make it clear that it’s okay if he can’t drive you to the hock shop to get the table and chairs. This isn’t about that. Make it clear to him that you’ve decided it’s better to have a strict no-alcohol rule in your apartment. Just so there’s no misunderstanding between you two.

It’s not that you can’t be around alcohol. You can control yourself. You were only trying to be a good host. It’s not like you were using him to prove a point. Or for some kind of voyeuristic thrill. You could go to a bar if you wanted that. It’s not against the law to drink in public. Or in private for that matter. Just make it clear that he’s welcome to come by any time he wants.

You feel better sorting this out in your mind, even when you realize (not without some disappointment) that it’s too late to say any of this to Jerry now. Anything you say to him at this point will seem too forced. Too needy.

You know what Jonah would say. He’d say you were trying to push your luck with that second beer. He’d say you were trying to put the gold stamp on your recovery. Hoping to put the last six months behind you. Looking for a clean break. Any excuse to not go to meetings anymore. It ain’t that simple, Marty, he would say. Nothing clean about the break you’re looking to make.

***

None of this changes the fact that you need to get that table and those chairs. It becomes a point of pride now to do it on your own. You could always rent a car for the day, but you decide to save some money and take the bus. It’s not even a dozen stops. Shouldn’t be too crowded early morning on a Saturday and sure enough you have your choice of seats on the way to the hock shop. Coming back is a different matter and you board the bus gripping the large square card table and its folded-in legs with one hand. The fingers of your other hand are curled tightly around the seats of both folded metal chairs with the rounded tops of their backs jammed firmly into your armpit. You manage to set down the table and lean it against your leg as you dig into your pocket to flash your pass at the driver.

Gripping the table again, you shuffle along the aisle, edging past the standing passengers. Opposite the rear doors is a nook between seats where you are able to lean the table and chairs. There’s a moment of rubbing the circulation back in your fingers before the bus lurches into traffic and you grab the leather strap above to keep from tumbling into the aisle.

Part of your brain is focusing on the rear exit doors and judging whether you can edge your furniture-laden self through the opening and negotiate those two steps onto the curb. But another part of your brain is aware of something hovering almost insect-like in your peripheral vision. Your eyes dart and scan the long seat in the main section of the bus with passengers sitting shoulder to shoulder, trying not to stare directly at the crotches of those standing in front of them. One pair of eyes are trained on you but more disconcerting is the purple tear-shaped mark on the woman’s face. At first, it seemed to be a bruise. Maybe a tattoo.

Then you remember that it’s a birthmark. That’s what she told you anyway. It all comes back, to that time you spoke to each other outside the Oasis Center. You were on the veranda one night having an after-meeting smoke. She was passing by on the street. She had been ragging you, mouthing off against AA and the 12 Steps. You had finished your smoke and asked if she had an extra. She had a pack wedged in her bra strap, waving it at you, taunting you by saying you could have a smoke only if you joined her for a drink.

For a second you meet her eyes, her smirk of recognition, then return your attention to the rear doors. You tighten your grip on the hanging strap, letting your body sway with the stop-start movement of the bus. Before you know it, the driver calls your stop and you scramble to grab up the table and chairs, teetering to keep balance as others make room for you to sidle and squeeze out of the rear doors, misjudging the step so the chairs slip out of your grip and clatter to the sidewalk.

Exiting passengers step around you. Holding up the table on its side, you crouch to get the chairs but someone gets to them first, each chair grabbed up and tucked under blue-veined sinewy arms sticking out of the frayed and oversized holes of a sleeveless jean jacket. Still crouching, you stare up at the tear-shaped birthmark. Squinting as if at a dark purple drop of blood in the sun’s pale glare.

-I got them, she says.

-It’s okay I can take them myself.

-What’s your problem, I’m helping you. Where we going?

You’re sure that any minute she’s going to take off with your chairs but she stands there waiting.

-I can’t hold these all day. Where to?

Grateful that you can now use both hands with the table, you lead the way along the two blocks to your apartment, looking back every now and then to make sure she is following.

***

You straighten and lock the table legs in place as she walks around the apartment, scrutinising what little there is to see. You’re not sure how she talked her way in and what she is still doing here. Behind the kitchenette counter, she comes up with the two empty Budweiser bottles from under the sink.

-Well, well, what have we here?

You explain about Jerry ordering the pizza although you have no ready excuse as to why you put the bottles under the sink rather than throwing them away.

-Just forgot about them, I guess.

-Out of sight out of mind.

-Something like that.

When the table is finally up on its legs by the kitchenette counter you place both chairs opposite each other, as if they are waiting for some intimate rendezvous to take place.

She sets the beer bottles on the counter.

-Y’know. So you won’t forget about them. I’m Karly, by the way.

-Marty.

-Marty. Like McFly.

-McFly?

-Y’know, from Back to the Future. Michael J. Fox? I love that flick.

-Oh yeah, right.

You remember taking Dani to see it for her tenth birthday when it first came out. Hard to believe that was ten years ago. A different time and place.

-So, thanks again for helping with the chairs.

Dismissing the hint, she comes around from the kitchenette and heads for the futon sofa. She collapses onto it with a muted thud from her wiry frame and kicks off her translucent plastic high heels, crossing and recrossing her legs. The rips in her skinny black jeans show off pale thighs and bony scabbed knees. She briefly inspects the chipped green polish on her toenails, takes a pack of Benson & Hedges 100s and a Zippo from her jean jacket pockets, and lights up.

-So, Marty. Have you been back yet?

-Back?

-The Oasis Center. Have you been back yet?

You retrieve the ashtray sitting on the two stacked milk crates (rescued from the alleyway behind the building where the dumpsters are) that now act as a side table next to the futon and empty the overflowing butts and ashes into the plastic flip-top trash can in the kitchenette.

-Not yet. Still getting settled in.

-You seem to be doing okay. Got a nice little set-up here.

-The table and chairs help.

You consider putting the empty beer bottles back under the sink then decide to set them by the door so you’ll remember to take them next time you go out.

-Got anything to drink? Something cold maybe?

Fair enough. One drink. Then she’s gone. You get a family-sized plastic bottle of Coke from the fridge and pour a glass, add ice then set it and the empty ashtray on the milk crates. Grabbing one of the chairs, you straddle it back-to-front, close to the ashtray, and light up a cigarette. This is your first real chance of getting a good look at her in the yellowish-grey light sifting into the apartment’s only window. She must be a hundred pounds at most. Flinty cheekbones create a rice paper complexion on which the tear-shaped birthmark can be read as a resilient stain, or at this angle of repose, a suggestion of something unpredictable. The jean jacket is partially buttoned and the pancake sag of half-hidden breasts tells you she is wearing nothing underneath. Her presence seems misplaced, as if she has appeared out of thin air. An apparition you may or may not have conjured yourself.

-Sorry I can’t offer you anything more than Coke.

-This’ll do for now, she says and takes a sip of her drink, punctuating it with an exaggerated sigh of refreshment that feels like a private joke, most likely at your expense.

She swings the topic back to the Oasis Center, how you liked it there, and why you left. You explain that there was nothing specific, it was merely time to leave. You’d been given a six-month sobriety coin and that seemed to signal something inside you, some kind of turning point. Although you don’t say this to her, you have lately come to think of it as a point of no return.

-I never saw one of those things. Can I see it?

-What, the sobriety coin?

Your first inclination is to lie and say you lost it. That’s what you would probably say to Jonah and everyone back at the Center if they asked. It’s what you sometimes say to yourself, just to try it on and hear how it sounds in your mind. Why you tell Karly the truth, that you left it on purpose at a diner along with the waitress’s tip, isn’t apparently clear. It’s not like it’s something you have to get off your chest.

-I get it. They give it to you like a reward. But out in the real world it ain’t even worth the price of a glass of water.

She stabs out her cigarette in the ashtray (almost a smouldering filter by this time) and immediately lighting another one. You would never have put it quite like that but agree all the same. There was that flask with the inscription that you’d been given for being a good salesman. Also, a kind of reward. Later hocked it when you quit drinking and got a measly ten bucks for it. So maybe she has a point.

When she asks if you have a sponsor your emphatic no draws a gust of hoarse laughter from Karly that trails off into a brief spasm of coughing. You feel embarrassed, caught out somehow by the inadvertent forcefulness of your denial. You try to compensate by explaining that you’d had some offers when you first got to the Oasis Center.

-These were guys who’d been sober for a few years. They didn’t actually live at the Oasis Center anymore. They’d moved out but continued to go to meetings there. They seemed like good eggs for the most part, but there was something about the whole idea that rubbed me the wrong way. These were guys who were very serious about working the steps and it was obvious that sponsoring me was as much about helping their own sobriety as much as mine. I guess there’s nothing wrong with that in itself, but I could see they were all about handing down their hard-won wisdom to someone. Maybe it made them feel important or useful or something. To be honest I wasn’t in the market for some kind of mentor.

-Hey, you don’t have to convince to me.

She takes a healthy swallow of Coke then swirls the ice in her glass like she’s holding court in some dimly lit booth at a cocktail bar.

-You’re preaching to the converted, my friend.

Without going into too much detail she says her brief stint at sobriety was five years ago. She didn’t make it past a month, but in that time, she averaged a couple of meetings a week. The ex-nun turned accountant who ran the meetings in the back room of a community centre offered herself as a sponsor and Karly had accepted.

-Sally was, like you said, a good enough egg. Everyone at the meetings still called her Sister Sally. Even though she’d been excommunicated, but that’s a whole other story, you could tell she liked it. But Christ almighty that one could preach the AA gospel like it was Bill W himself who died on the cross for our sins. She just traded one religion for another. A month of that brainwashing mind control was all I could take.

When you mention that the closest you came to having anyone like a sponsor or mentor was Jonah she sits up and takes interest. Turns out she once had a run in with him when he caught her and one of the residents smoking a joint in a fenced-off area behind the Oasis Center. He had warned her about trespassing on the property and threatened to call the police.

-I guess that’s why I gave you such a hard time that time I saw you coming out of there, she says.

You remember how angry you were with her at the time, how you wanted to smack that tear-shaped birthmark right off her smug face. It shocks you slightly to hear yourself assure her that it’s all water under the bridge now. The shock quickly dissipates into an awareness that the whole six months in the Oasis Center have receded farther behind you than you thought. You enjoy a moment of genuine relaxation for the first time in you don’t know how long.

Still, you feel it’s only fair to give Jonah his due. His door was always open to you and his support was instrumental in getting you through some very difficult patches. Karly merely nods while listening to all this, which begs the question you’ve been avoiding since you moved into this apartment – why haven’t you called him? At least tell him you’re doing fine. Sure, he would get on you about coming to a meeting. Is it that you’re afraid you won’t be able to say no to him? Or maybe you’re afraid that you’d acquiesce? In your heart, you know you couldn’t bear stepping into that lunchroom again with all those others, most of whom are there because attendance at the meetings is mandatory for residents of the Oasis Center.

-I just thought of something totally crazy.

Karly sniggers into the brownish dregs of Coke and melted ice at the bottom of her glass. If you didn’t know better, you’d say she was a bit looped. Maybe she’s on a sugar high.

-What is it?

-Why don’t I be your sponsor? I mean it’s obvious you want to cut ties with the OC. I get it. I know what sponsors do, but I ain’t gonna preach a lot of AA holy thunder at you. I’ll just be there when, y’know, you’re feeling like you wanna give up the ghost.

You don’t say anything at first, merely let her words sink in and take a spin or two around your brain. When you’re almost convinced that she’s being serious you still don’t say anything.

-Oh well. Maybe you’re not looking for a sponsor. Maybe you think you got this whole thing licked on your own. You wouldn’t be the first.

-How could you be my sponsor? I mean, you still drink. How would that work?

-I told you it was crazy. Just forget I said anything. I can see you have things all figured out. What the hell would you want my help for? Just remember Bill W was a straight-up acid head and all the recovery converts still worship at his shrine.

With that, she leans over and puts her shoes on.

– Thanks for the drink.

At the door she stoops and picks up the two empty beer bottles.

-As your would-be sponsor I’ll just take these. Out of sight out of mind.

She lets herself out and closes the door behind her. The impulse to go after her flutters somewhere within your brain’s crossed circuitry and you rise up from your chair. But you merely put the chair back in its place at the table and check the fridge to see what there is to make for lunch.

***

Maybe you think you got this whole thing licked on your own. Her words keep coming back, sometimes as a taunt, sometimes as encouragement. In either case, they reverberate within a locus of solitude. You can also imagine Jonah saying the same thing to you, but somehow it would come out differently. With Jonah, it would be a warning that this is not the road to go down. Karly’s tone also carried a shade of caution, yet came across as a kind of a dare.

It had often been repeated at meetings, usually by non-residents of the Oasis Center who’d been sober for a few years (those old-timers, as you thought of them, although some were almost ten years younger than you), that relapse is inevitable. How and when it happens is another matter altogether. The relapse stories varied, but for the most part carried one similarity: a trigger of some kind. Usually something unexpectedly. You always assumed this was just their way of putting the fear of God into the residents. A way to seem more worldly-wise, all the better to put themselves out there as potential sponsors. You assumed that Jonah allowed them to keep coming to the Oasis Center meetings, even after they moved out, specifically for that reason. Maybe that’s why he encouraged you to keep coming back to the Center for meetings. He recognized your intelligence, your ambitious nature, and maybe saw you as prime material to be groomed into a future sponsor.

Frankly, it was one of the reasons you were anxious to get out of there as soon as you could and why you’re reluctant to go back.

Maybe that’s also why you’re reluctant to answer the phone one night, thinking it might be Jonah reaching out to you. It turns out to be Roz phoning from New Jersey to discuss some outstanding debts you incurred back there. You’re thrown off your guard by how good it is to hear your wife’s voice. At that moment you miss her and Dani more than anything else in the world. When you ask about your daughter, Roz lets it slip that Dani is pregnant.

-Who’s the father?

-A boy she’s been seeing.

-And what about school?

-She’s still in school. I don’t know what to tell you, Marty. She wants to have the baby. She’ll stay in school as long as she can.

-How long have you known?

-I don’t know, about a week maybe. What does it matter?

-What does it matter? And you’re only telling me now?

-I didn’t mean to, Roz says, her voice cracking.

-I don’t understand! What do you mean you didn’t mean to?

-Please don’t yell at me.

She tries to catch her breath between sobs. You light a cigarette to give both of you a moment to calm down.

-When was she going to tell me? Or was she leaving that for you to do by accident?

-You don’t have to be like that, Marty. It’s complicated. She wants to tell you herself. She just didn’t want you to get upset now that you’re starting to get yourself together. And now she’ll probably get mad at me for spilling the beans.

You take a deep drag on your cigarette. The angry red ring at the ash’s rim. You’re standing in the kitchenette and realise the ashtray is over by the futon. The phone cord won’t reach that far and in frustration, you flick your ash in the sink.

-Is this about the money? Is that why you told me? I’ll send you what I can but right now I don’t know how much that will be.

The accusing tone in your voice echoes back as an ineffectual whine.

-Really, Marty? You think I was using our daughter’s pregnancy to pump some money out you? Are you kidding me? You left me here with all this. All these debts to deal with. Condo fees are going up. I’m still trying to pay off the credit card you maxed out when you took your little gambling holiday to Vegas.

-You think all this has been a holiday? Detox? Rehab? This shithole I’m in?

-All I know is you’re there and I’m stuck here on my own. What am I supposed to do?

***

For the next couple of days, you find yourself brooding on the bus, at work, shopping for groceries. Eating at the card table while staring at the empty chair opposite you, as if stood up by a dinner companion, makes the apartment feel smaller and emptier. You find yourself not bothering to pull out the futon into a bed anymore, preferring to fall asleep in tee shirt and boxers on the sofa. At various times you consider calling Dani at your mother-in-law’s to confront her.

Then you decide it’s better to wait until she calls you. Yes, let her tell you in her own time. The rabbit hole you unexpectedly find yourself burrowing into is memories of Roz’s pregnancy when she was carrying Dani. Being home only on weekends because you were the regional sales manager for your company’s office in Victoriaville, a small town in southern Quebec (almost 200 kilometres from Montreal, a four-hour drive one way), and living in a motel there during the week. More and more that’s what this apartment is starting to remind you of. The endless impermanence.

The frustration of being so far from Roz when she needed your support was one thing, but it was a pregnancy that came on the heels of your mother’s death. What should have been a sign of renewal after a loss, a gateway to healing, only plunged you deeper into an unresolved limbo. That was when the drinking really started. The bottle of Chivas Regal that lived in the desk drawer of your office for appearance’s sake, strictly to break the ice with clients, soon started making its commute to your motel room and then back to the office in your briefcase.

When the call from Dani comes on the usual Sunday evening, you aren’t sure what you’ll say to her. As Roz had predicted, Dani is angry at her for telling you about the pregnancy. She wanted to tell you herself.

-Don’t blame your mother. She’s under a lot of pressure. She’s worried about you. So am I. It’s hard, Dani. You in Montreal, your mother in Fort Lee, me here in Vegas. We’re all so far from each other. It’s not supposed to be this way.

-That can’t be helped. I wish I could have told you and Mom together. But I’ve got Bubbe Rita here. I don’t know what I would have done without her. She’s been great.

At the mention of your mother-in-law, who was also a source of strength to you after your mother’s death, your gratitude is punctured by a stab of guilt.

-I wish you could have known your other grandmother. I miss her.

-I know. But you never really talk about her.

A moment’s silence lets you glimpse the chasm of bottomless grieving that you have never been able to give voice to. You change the subject to the father of Dani’s baby. Dani tells you of someone named Caleb, a journalism student and musician. You can tell by her respectful description of him – caring, funny, supportive – that there is something she is holding back. You leap on whatever comes to mind. Maybe he’s a drug addict. Or worse, mentally or physically abusive. But you don’t say these things out loud.

-Are you two going to get married? What’s the plan?

There is another silence but this time from her end and you wonder if she is looking into her own internal chasm.

-The truth is … I broke up with him the other day.

-Why? What happened? What did he do?

-He didn’t do anything. The thing is, he still lives with his mother. And there’s nothing wrong with that. She’s very nice. I have nothing against her. But we agreed to tell her about the baby together. Caleb was good about waiting. I knew he was eager that she should know. His father is dead and it’s just been him and his mother for the past ten years. They’re very close and I think he needs some breathing space from her sometimes. I think he sees the baby as an escape from her.

-From what you’re telling me, it sounds like he wants to take on the responsibility of a being a father.

-I guess … He says he does. It’s just – he’s ready to give up a lot to do this. Like playing in his band. He’s a very good musician. He loves music. But he’s ready to sacrifice all that just to prove he’s mature enough to be a father. It’s kind of perverse, don’t you think?

You aren’t sure how to answer. You yourself had always done what you thought was expected of you. Find a job in a good company in Montreal, work your way up the ladder to Sales Manager after you were transferred to the New York office until you were eventually downsized a couple of years earlier, just before Christmas in ‘93. You weren’t that much older than Dani when you got married and started a family. And now here you are a few thousand miles from her and Roz and unable to offer any help or guidance. Strangely enough, you find yourself feeling a bit sorry for this Caleb kid.

-He has rights, doesn’t he? You’re carrying his child.

-I know, Dad. It’s not like I plan to get a court order against him or something. I don’t want to keep him away from his child. But I don’t have to chain myself to him either.

-That sounds a bit harsh.

-I didn’t mean it like that. Look, Dad, a few months ago I was all set to have an abortion.

-You were? Did your mother or your grandmother know? Obviously, you weren’t going to tell me.

-Nobody knew, okay? Well, Caleb knew. He was against it. But that’s not why I didn’t go through with it.

-What happened?

-I don’t really know how to explain it. It felt like that was the expected thing to do. Have an abortion. Free myself so I could live my life. But I didn’t know what I was freeing myself from or what I was supposed to do afterward. Finish school? Travel? Write that first novel? I plan to do those things anyway. It’s not just that I have a life growing inside of me. In a way, it’s my own life growing inside of me. It’s like I’m going to give birth to myself … if that doesn’t sound too crazy.

-It doesn’t sound practical, that’s for sure. You need to think this through, Dani.

-I have thought it through, Dad. I knew that if Caleb and I told his mother together that would be it. I would be stuck with him forever. I know how bad that sounds, but I had to break it off between us. I had to take a stand. I know you probably don’t believe me, but I did it for the both of us.

-I can’t say I understand any of this, Dani. But if it helps, I believe you.

And you do. Yet, the more you think about it in the days that follow the more blame you feel for her decision to do this alone. She obviously sees this Caleb kid – for all his willingness to take on the responsibility of raising the baby – as a momma’s boy who’s never going to escape the apron strings. And for that, she sees him as unfit to be a father. You can’t help wondering if you are the role model, the unfit father, by whom she is judging this boy and basing her decision.

It’s the unfairness of her decision, the selfishness of it that tips you closer toward that familiar inner chasm. If only she would give the boy a chance, let him prove himself. He might actually surprise her and sever all ties with those so-called apron strings that truss him up like a lamb for the slaughter. He might find a way to duck out from under the impending clouds of everyone’s expectations and escape the dutiful choices he will regret for the rest of his life. Whether any of this still has to do with Caleb becomes obscured by the foggy drift down this gradual slide into murky introspection.

What could never be reconciled after your mother’s death are the alternating currents of anger and guilt at her disappearance. The deep wound of abandonment, for which you cannot help but blame her, depletes your resources and leaves you with nothing tangible except for the knowledge of the dark pit within. Your unshakable belief that the wild rollercoaster you watched her ride throughout your youth – the slow climb from carefree well-being to a manic apogee before she eventually plunged into an abyss of tears and isolation – somehow found its way into your own bloodstream.

The edge that pushed you to succeed as a salesman eventually spilled over into an excess of bravado whose only outlet was the racetracks and backroom poker tables. To be followed by a stretch of near-paralysis from remorse and self-pity that felt like nothing less than a punishment for merely existing.

And if all this really is her genetic legacy passed down to you, what else is there left but to continuously find yourself at the same old cul-de-sac at every turn? What hope is left to you but to take the Möbius strip of your grim reality and fashion it into a noose to end it all?

***

It’s harder to sleep at night and you find yourself straggling in late to work a couple of times. Mr. Childers gives you a friendly warning and you work through your lunch hour to make up the time. Jerry remarks that you look tired and seem preoccupied. He kids you about keeping late hours and asks if you’ve been putting mileage on the futon with some fox. All you can manage is a weak smile and continue unloading metal drums from the trailer of an eighteen-wheeler at the loading dock.

On your way home you look out the bus window and see the same liquor store you pass every day and decide to get off a couple of stops early. Sidewinder’s Liquor Boutique, its display window plastered with a colorful array of beer, whiskey vodka, and other assorted labels, is on the opposite side of the street but you don’t cross right away. There’s a moment of hesitation when you seriously believe you’re going to turn around and walk the six blocks home just for the exercise. But you stand there at the corner and watch the traffic lights change colors as if in a game of chance and one of those colors will be the signal that tells you what decision to make.

The next thing you know the light turns green and you’re crossing over. On the other side you stop short of the door for a moment, look around wondering how you got here then push the door open before some capricious gust spins you around and sweeps you back across the street. Greeted by an electronic tone as you shuffle past the threshold, you slow down as the door closes behind you.

Now something shifts in the atmosphere and you almost float from aisle to aisle, passively surveying shelves with different colored bottles. You haven’t decided on anything yet and, who knows, you might still leave empty-handed, although the always dependable Chivas Regal has not escaped your eye. The floating sensation soon starts to lag, as if the soles of your shoes were dragging through wet sand. A slight impatience pushes against the sluggishness and the burnished ambers and deep burgundies and clear elixirs trapped in various glass shapes and sizes make your eyes itch. You rub them and wipe your nose on your sleeve. The next thing you know you are cradling a pint of Ballantine’s in your palm and making your way to the cashier. You fish your wallet from your windbreaker’s outside pocket before you get there and have the ten-dollar bill in your hand as the purchase is being rung up. It comes to twelve dollars and forty-two cents. You peel a fiver out of your wallet and are almost tempted to tell the young Pakistani man to keep the change. But you wait until he hands you the two bills and coins then bags the pint.

Back outside you didn’t expect to feel so conspicuous, and you try to shove the bagged pint into your windbreaker’s other pocket but it won’t fit.

-Hey, McFly. Must be celebrating something.

Startled, you turn around and the purple tear-shaped birthmark is all you can see as you shift the paper bag from one hand to the other and back again.

-Oh, I’m sorry, says Karly with a feigned look of innocence. Did I just scare the crap out of you? Don’t worry, McFly, you got nothing to worry about from me. Now be a good boy and hand the bottle over.

She holds her hand out and you stare in disbelief at her pale bony fingers.

-What?

-Did you think I was joking last time when I said I wanted to be your sponsor? Now hand the bottle over and we can talk about this.

-I’m not handing it over.

-Fine, if you want to be like that. But I’m not leaving your side.

-You aren’t my sponsor.

-But I know where you live.

***

What does it mean anyway, to have the upper hand? One’s position in any kind of negotiation can only be gauged from a point of self-interest. As Jonah once told you, self-interest can often end up being its own blind spot.

You’re sitting at the card table. Karly is seated opposite you. The pint of Ballantine’s remains unopened in its paper bag on the table. Now that it’s actually in the apartment you feel that the situation is manageable while the bottle is still unseen. Karly suggests you take it out so you can face head-on the decision you made to purchase it. You are adamant that the bottle stays in the bag.

-Better it than you, I guess.

Neither of you laugh.

-What the hell are you doing here anyway? Expecting a real drink this time?

-Are you offering?

-Some sponsor you turned out to be. Go ahead. Crack it open.

-That’s not how it works, McFly. See, all those hand-holding sponsors do is listen to you pour your heart out then tell you to go to a meeting and pat themselves on the back that they were there for you. I have a different way of doing things. I’m not here to save you from yourself. I’m here to make you look at yourself. You’re not gonna do that by staring at a paper bag and pretending nothing’s in it.

You reach over and ease your hand into the bag’s open mouth, feel for the bottle’s short neck and slowly extricate it from the bag so as not to disturb it. You set the bottle on the table next to the still-standing paper bag.

One empty, the other full.

One open, the other sealed.

Where’s the leverage? You aren’t dealing with Jerry now. Poor sap made a mistake by ordering beer with the pizza and you made him pay the price. He had to drink in front of you. To give him his due he took his medicine with a certain amount of grace.

-Congratulations, McFly. You’re past the hardest part.

In your mind, it’s not Karly talking but the tear-shaped birthmark addressing you directly. It’s the only part of her that you see most clearly. You get up from the table and go to the kitchenette. The first thing you do is unplug the phone. Then you get a couple of glasses from the cupboard, drop ice cubes in each then carry them back to the card table. Without sitting, you take the pint bottle from the table, twist the cap, and break the seal. Then you pour three fingers of Scotch whisky into one of the glasses and push it toward Karly. The other glass remains empty except for the ice.

-I count two glasses. You’re not joining me?

Your only reply is to take the bottle over to the futon. You can imagine the ice in the empty glass is starting to melt. In your mind it recedes into the background, getting smaller in the distance like an iceberg you barely missed while navigating the good ship USS Leverage.

You collapse onto the futon and stretch your legs. Whichever is the upper hand, you manage to raise it high enough to tip the bottle’s neck to your lips and drink.