In 1991, Leocardia Byenkya underwent an ultrasound that informed her to expect a baby girl. She chose the name Philomena. On January 16, 1992, her baby was born a boy. Filled with shock and surprise, Leocardia named her baby boy Mugabi.

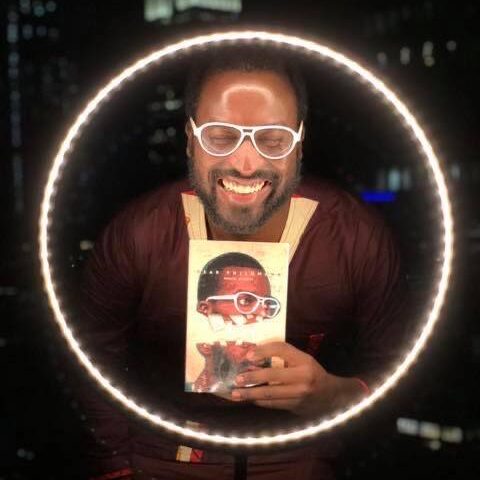

Today, Mugabi Byenkya writes for the angsty, confused, Black, Ugandan-Rwandan-Nigerian, disabled, and neurodivergent little human they used to be and still are. They published their magical realism memoir, Dear Philomena, in 2017, three years after the two strokes that changed their life.

We spoke with Byenkya about accessible writing, readers’ reaction to their work, and their upcoming projects. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

One of the most fascinating aspects of your work is the format. The story is told through songs, mail, social media posts, and such. What inspired this format for telling your story?

The primary inspiration behind the format was my disabilities. I was writing the book in the aftermath of surviving two strokes that gave me chronic pain, seizures, chronic fatigue, photophobia, hyperacusis, and difficulties with processing large blocks of text.

I wanted to write a book that was both accessible to me as the writer, but also accessible to disabled and neurodivergent people like me, who had difficulties or found it impossible to process large blocks of text. I’ve always been an avid reader, but after my strokes I couldn’t read conventional books anymore. I’d get through a paragraph and the exertion that entailed on my body would trigger a seizure. I turned to audiobooks with the immersive narrators, audiodramas, and comics.

Since publishing Dear Philomena, several disabled and neurodivergent readers told me it was the first book they’d been able to read in years. Non-native English speakers said it was the first English book they’d ever read. People who don’t consider themselves readers or have difficulty finishing books said they couldn’t put it down and/or read it in one sitting. This makes me happy, but simultaneously sad, as it illustrates the lack of accessible literature out there.

This novel is mostly autobiographical. Could you tell us about the parts that are not? What made you decide to include magical realism?

The parts that are not autobiographical are the parts where Philomena is speaking, as Philomena does not exist in the corporeal world. When my mother was pregnant with me, she was told to expect a baby girl and was over the moon. She chose the name Philomena and when I was born and assigned male at birth, she didn’t have a name to give me. My birth certificate literally reads Baby Byenkya.

I don’t ascribe to the gender binary. However, I’m male presenting, was assigned male at birth, and move through the world in most people’s eyes as a man. Writing the parts where Philomena is speaking was a thought experiment, where I could see how differently my life would have turned out if I was assigned female at birth, Muslim (a lot of my family is Muslim and I could have just as easily been born into the Muslim side), and able-bodied for my entire life. It allowed me to look at how different gender roles, religion, and ability would have shaped me.

Having Philomena in the text allowed me to vent in ways I couldn’t to my friends and family. It allowed me to merge personality elements of myself and of different real-life friends into Philomena. It allowed me to come to terms with my gender identity. It allowed me to provide a representation of what I aspire to in friendship. And it allowed me to acknowledge a part of me that I had long repressed.

What would you say was the most difficult part of writing this book?

The most difficult part of writing this book was the physical act of writing. I’d write for fifteen minutes, have an excruciating several hour long seizure as a result, and then be unable to write for the next day or two. I manage depression and suicidal ideation, and while reeling from an excruciatingly painful seizure, I often wondered if what I was putting my body through was worth it.

Slowly, over months, I was able to build up a writing tolerance and fifteen minutes of writing became thirty minutes of writing, which became forty-five minutes of writing. I’d still have violent seizures and I’d still have suicidal ideation. Honestly, it wasn’t until after the book was published and so many people told me about how the book made them feel seen and mended relationships in their life, how it book got them through the aftermath of a suicide attempt and made them recognize their able-bodied privilege, that I reconsidered what I went through being worth it.

Despite the trials and tribulations of the writing process, it was incredibly cathartic and helped me (alongside therapy) process all the suffering I’d been through. It helped me close that chapter of my life and move on to a new one and it helped explain to family and friends what I went through.

What advice would you give to writers like yourself, particularly to those with chronic conditions?

My advice to writers with chronic conditions is to not hold yourself to able-bodied standards. You are worth more than your work. So many able-bodied writers give advice about establishing a regular writing practice, which is impossible for people with chronic conditions like myself.

My disabilities are dynamic. They ebb and flow. I spent March 2020 to March 2022 largely bedridden and every time I tried to simply respond to a text or write creatively, it would trigger a seizure. I flashed back to the events of Dear Philomena a lot during that time, as I was in an eerily similar state. I went two years unable to write, but I had significantly better coping mechanisms than I did during the events of Dear Philomena and I was able to have poetry and essays published that I’d written prior.

Those two years, I was unable to write, but that didn’t stop me from having ideas. I jotted them quickly whenever I had the capacity and have already written some of them. I was able to write comics that were professionally published and paid for (a childhood dream come true!) using “The Marvel Method” with my collaborator Paul Bourgeois.

Writers are often defined by their writing output, so I would encourage any writers like myself to not do that. Our ability to write may come and go, but that doesn’t make us any less of a writer. Experiment with forms of writing that are accessible to you as a writer, as I did. Pace yourself. Write when you can, and be grateful for the ability to write, as it can be taken away from you at any time. Managing our health is often our first priority, and there’s no need to be ashamed of that. If any writers want to reach out to me directly, they can do so at mugabibyenkya@gmail.com.

A wonderful thing about your book’s format is that it is more accessible to disabled readers. Do you have advice for writers that want to make their books more accessible?

I will refer frequently to the wonderful Ettie Bailey-King, from whom I learned cognitive load theory, the latter of which states that, “Working memory is only able to hold a limited amount of information at one time. If we overload it, this creates errors and interference with the task at hand.”

This so accurately describes the countless excruciating seizures I had after my two strokes, whenever I attempted to read, process text or write. To avoid overload, I:

- focus on simple writing

- use everyday words

- use short simple sentences

- use short paragraphs

- use sentences that stop when you naturally take a breath

- get straight to the point

- write for scanning

Additionally:

- contractions, figurative language, and idioms can be harder for some people

- write for screen readers and use typefaces with clean, distinguishable shapes

- tell stories, as they are more memorable, and cut straight to people’s hearts

- ask people what their access needs are

- numbers can be tricky for people with dyscalculia

- try what comes out when you speak and not overthink it

Moreover, short frequent messages work better for cognitive load than longer, less frequent messages. All in all, different things work for different people and there is no one answer when it comes to accessibility.

Is there anything else you would like to share?

The central thesis of Dear Philomena is that sometimes you can’t overcome, you can simply manage. I wrote this book as a counter to all the disability narratives I was seeing around overcoming and if you tried hard enough, you can overcome. As I quote from rdeforest in Dear Philomena, “When you propagate the myth that subjective problems can be surmounted by positive thinking, prayer, and hard work you are propagating the myth that disabled and disadvantaged people are not trying hard enough. That myth is destructive to our culture.”

Additionally, anyone interested in purchasing a copy of “Dear Philomena,” can get a paperback via Caversham Booksellers or an e-book via Amazon. Anyone interested in purchasing my debut mixtape, “Songs For Wo(Men) 2,” which serves as a follow-up to Dear Philomena, but is also a stand-alone project, can get a physical cassette or a digital album via BandCamp, courtesy of the amazing independent record label “Hello America Stereo Cassette.”

Anyone interested in finding out more about my work/reading or watching or listening to interviews I’ve done/reading poetry, prose, drama, comics, essays and songs I’ve had published can visit my website at www.mugabibyenkya.com. Lastly, register for the amazing panels Knee Brace Press will be having for their summer series (I’ll be one of the panelists!) for free via kneebracepress.com/summer-series.