I grew up in a Washington Heights, Manhattan apartment filled with music: my parents’ classic music and Broadway musicals, my older brother’s folk and rock. We had hundreds of record albums; often many of the covers were often spread across the living room floor in front of our mid-century, blond-wood console Hi-Fi.

I was given piano lessons from an early age on a used upright piano so old that it had brass candle stands attached at each end. And though my sweet-voiced, elderly Russian teacher said that I had “good expression,” whenever she launched into explanations of music theory, I went blank. It didn’t matter that she tried teaching me the various mnemonic devices for reading the musical staff and identifying notes: I couldn’t seem to keep the information in my head, and it left me feeling stupid.

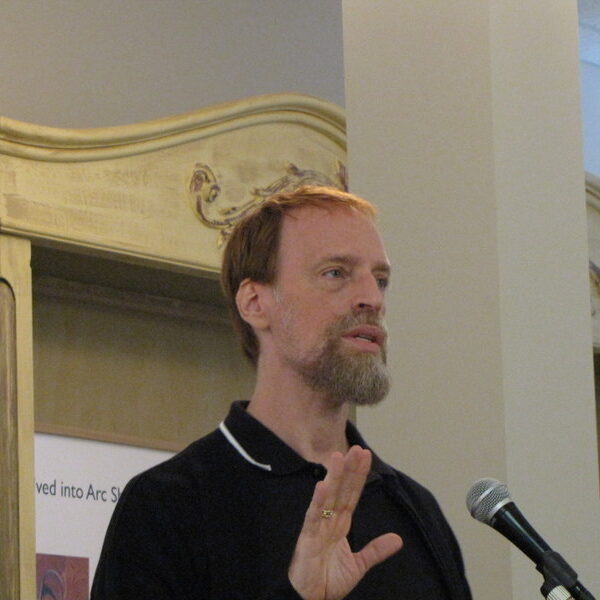

Fast forward decades later when I’m studying voice with a dynamic, young, ebullient teacher at Michigan State University. He starts explaining “Solfège”—that is, do-re-mi-fa-so-la-ti-do starting with the note C or any note you choose. Using syllables to replace the notes is supposed to help you with your sight reading, help you identify notes quickly and sing them correctly.

The blank returned, and the fluorescent lights in the practice room, filled with black plastic stackable chairs and music clustered around a black Steinway baby grand, seemed brighter than ever — bright enough to make me feel exposed, anxious, and ashamed. That was a real switch because for months we had been working beautifully together, in such harmony (pun intended) that he seemed to read my mind —”You were thinking about that note. Don’t think. You have a great ear, trust your audiation.”

After the lesson where we’d spent some time on Solfège, I ventured onto Google and eventually discovered a term I had never encountered before: number dyslexia. Technically called “dyscalculia,” it’s a type of neuro-divergence and parallel to dyslexia. People with number dyslexia may not be able to read maps, judge distances and speed, or tell right from left, and they often have trouble with arithmetic and mathematics. Bingo!

I felt bathed in golden light of understanding: my past opened up to me in a whole new way. In elementary school, I could never remember my multiplication tables and my fifth-grade teacher called me “dumb” because I kept flunking quizzes no matter how hard I studied. This frustrated my mother, who was a math whizz — and whose father had been a statistician. When it came to mathematics in junior high school and high school, I was even more lost, and tutoring didn’t help.

As an adult, I have consistently had trouble balancing my checkbook, often gotten a recipe confused by skipping a step, and frequently found myself puzzled while trying to read newspaper charts about almost any subject. It’s as if they suddenly switch to a language I’ve never studied or even heard before (and I speak good French and German). During my Google search, I found that when it comes to singing, people with number dyslexia can have trouble sight reading music and understanding music theory. However, like me, they’re often outgoing, artistic, literary, and wizards at grammar and vocabulary.

Learning about my neurodivergence has made me feel free. It explains decades of experiences and I feel fascinated to understand myself in a whole new way. If I had known this about myself back in elementary school, I wouldn’t have had to deal with so much anxiety then and in the years to come. I definitely would not have been forced to sit in the “Dumb Row” in fifth grade whenever we had a math lesson.

I shared the discovery with my voice teacher, who was grateful. Because he could have current or future students who don’t seem to understand theory or who have trouble reading music. And it might not be a question of how hard they’re working — it might just be who they are.